By TIM THOMAS

Special to Hays Post

In December 1905, the remains of soldiers who had long been buried at the historic Fort Hays were unearthed for reinterment at Fort Leavenworth. What was initially just an administrative move took a macabre turn. Rumors began to spread that some of the buried may not have entered their graves entirely dead.

Fort Hays was established in 1867 and was a key post on the western frontier until its decommissioning in 1889. In 1905, the bodies of soldiers who had died at the fort were to be moved to the Fort Leavenworth National Cemetery. The bodies in Fort Hays cemetery had been buried for almost 40 years at that point, and many were victims of a cholera epidemic at the post.

The initial report from the Ellis County Republican was published on Dec. 23, 1905. The paper mentioned that during the exhumation of soldiers, “a number of strange things were brought to light.”

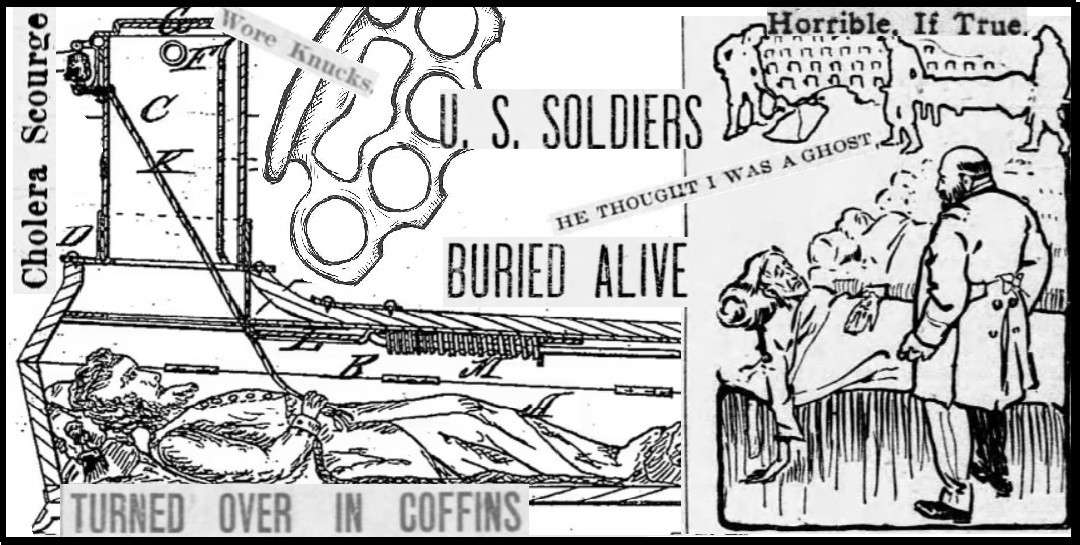

These included: a man buried with brass knuckles on his hands, a man whose only remains were hair and feet that were encased in immaculate socks and shoes, hair of the dead turned a reddish color (it was supposed from the clay earth in the cemetery), and “a number of other odd conditions reported by the men employed in digging up the bodies."

The most disturbing detail reported by the Republican was the condition of at least one man.

“In another grave, the body was found lying on its face with the arms and limbs drawn up as if in agony.”

Six days after the initial reports by the Ellis County Republican were published, a story popped up in the Fort Leavenworth Post. This story featured an account from a Hays businessman, J.H. Wood, who spoke with a newspaper representative.

His account stated that there was “unmistakable evidence” that men were buried alive, and the “gruesome evidence was plain in a number of cases” according to the Fort Leavenworth Post. The Post also made mention of the fact that victims of cholera were buried rapidly, which could lead to a person mistakenly being buried alive.

That same day, December 29, 1905, a short article ran on page one of the Kansas City Journal with J.H. Wood’s account of live burials at Fort Hays. From there, the news spread like wildfire, with articles appearing in newspapers all over the country republishing Mr. Wood’s account.

While the story told by J.H. Wood was going the early 20th century version of viral, another report appeared in Nebraska. On Jan. 2, 1906, The Hastings Daily Republican published a news note from Omaha. A Mr. and Mrs. C.E. Black had recently returned from a trip to visit Mrs. Black’s mother in Hays.

It seems Mr. and Mrs. Black had been in town during the exhumation of the bodies, and the Blacks had a gruesome report.

According to the Hastings Daily Republican, “Some of the bodies had turned over, others had the legs drawn up to the neck, and in others the hands were filled with hair that had been torn from the scalp."

The Daily Republican mentioned that the evidence of soldiers being buried alive came from the section of the cemetery where the cholera victims had been buried.

Modern medicine has made it so that many people take doctors' knowledge and abilities for granted. Medicine in the 1800s was not nearly as advanced, and people of the time feared being mistakenly pronounced dead and put in an untimely grave.

So great was this fear that Edgar Allen Poe published a story, “The Premature Burial," about being buried alive in 1844. There were also two different patents for safety caskets to prevent live burial. In 1868, Franz Vester was granted a patent for an “Improved Burial-Case,” and in 1882, John Krichbaum received a patent for a “Device for Indicating Life in Buried Persons."

This fear was compounded by cholera, which, throughout most of the 1800s, would periodically tear through the country. A standard operating procedure for stopping the spread of the disease was to bury the dead as quickly as possible. Pairing this with overworked doctors and limited knowledge could theoretically lead to mistakes being made in properly identifying the dead.

J.H. Wood’s account of soldiers being buried alive had been reprinted in St. Louis area newspapers. One of those newspapers was the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, which published the account on Dec. 31, 1905.

There it came to the attention of Lawrence “Old Larry” Ring. Lawrence Ring sold newspapers in downtown St. Louis. He was a Civil War veteran of the United States Navy. After the war, he spent time as a government teamster, where he passed through Fort Hays during the cholera epidemic.

The 1867 cholera epidemic hit western outposts and towns particularly hard. While en route to Fort Riley, Elizabeth Custer, the wife of General George Armstrong Custer, was stopped in Ellsworth. There, she described the disease as so bad that there was not enough lumber, and coffins had to be improvised from hardtack boxes.

Fort Hays was not spared. At least 30 soldiers and over 100 local civilians would succumb to cholera in just two short months. While at Fort Hays, Lawrence Ring came down with cholera and was nearly buried alive.

“I had been sick but four days,” he said, “when they removed me to the deadhouse.”

According to Ring, a few minutes after his last rites had been read, he was carried off by hospital attendants. He was placed in the “deadhouse” but crawled out and returned to his cot to the surprise of the staff.

“When the doctor saw me on my cot the next morning, he acted like he thought I was a ghost,” Ring said, “it was the only bit of humor I recall out of my experiences during the plague.”

After recovering, Mr. Ring worked as a hospital orderly, where he likely would have interacted with the fort’s most famous cholera victim, Elizabeth Polly. Elizabeth is commonly known as the “Blue Light Lady” for her spectral appearances around the fort. During his time as an orderly, Mr. Ring attested to the speed at which burials occurred.

“I witnessed much misery,” he said, “I know too, that no time was lost in burying the dead, as the laws respecting interment of cholera victims were very stringent.”

That brings the story back to Hays and the question of whether soldiers were truly buried alive during the 1867 cholera epidemic.

The Ellis County Republican published a small note on Jan. 13, 1906. In the paper, it claimed regarding the possibility of people being buried alive that “Only one body was found bordering on this.”

This body, they claimed, was of the man who was found buried while still wearing brass knuckles. This was accounted for in a Dec. 30, 1905, letter to the editor by Hill P. Wilson.

Mr. Wilson stated the man was a soldier from the 38th U.S. Infantry. In 1868, the soldier had attempted to break into a house while wearing brass knuckles and was shot dead. The soldier was left dead in the house for people to view, which Mr. Wilson did and was then buried while still wearing the brass knuckles.

This account certainly explains the man wearing brass knuckles. Still, it does not explain the body that was found flipped over with its arms and legs drawn up “in agony” as originally reported by the Republican.

It also leaves the people who related their stories to other newspapers, J.H. Wood and Mr. and Mrs. C.E. Black. At the time, Hays was a small town with a population of less than 2,000. It is possible that rumors could have spread quickly. It is also possible that they could have witnessed the exhumations firsthand, as many newspaper reports at the time said it was a spectacle for the town.

After 120 years it is impossible to know and it’s probably true that the people of Hays may have wanted it that way to keep a dark tale from spreading about their home.

As stated in the Hastings Daily Republican, “The matter was being discussed as little as possible by the authorities, and no information was given out voluntarily.”