By CRISTINA JANNEY

Hays Post

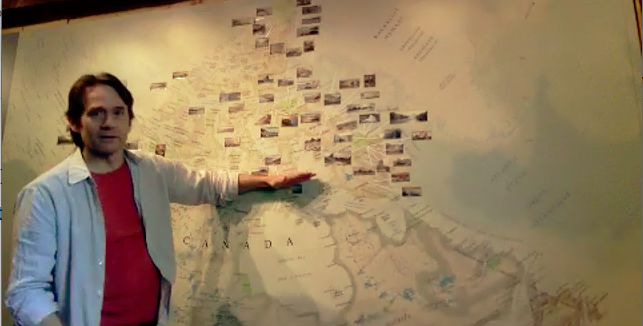

Cory Trépanier has spent the last 14 years exploring the Arctic, braving tough terrain and Arctic wolves, to bring the world images in film and art of the splendor of the landscape.

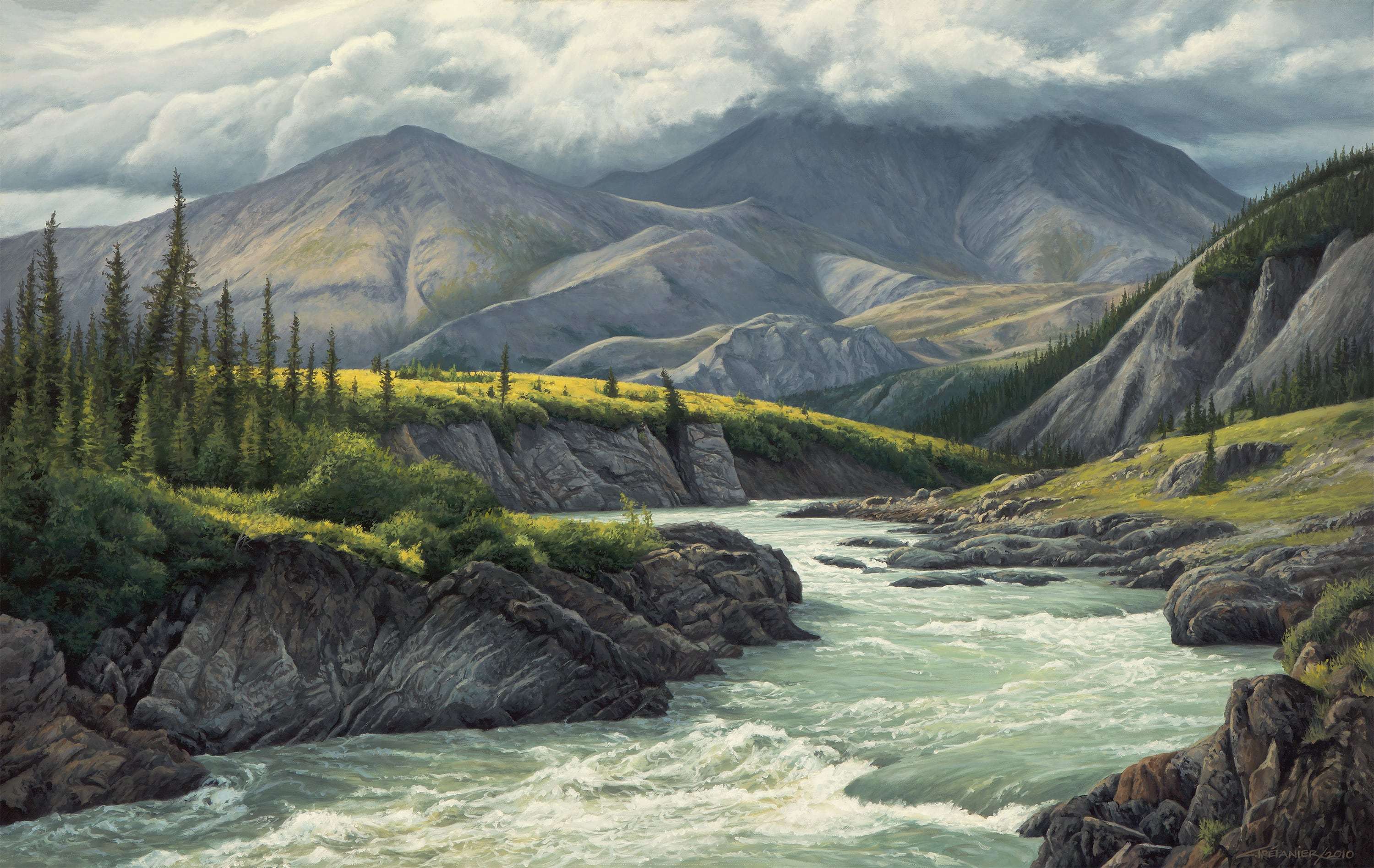

Trépanier's exhibit "Into the Arctic" is on display now through Sept. 1 at the Sternberg Museum of Natural History in Hays.

Trépanier, 51, who lives near Toronto, started to fall in love with the idea of a project in the Arctic in 2005.

"That was when I started to see images of the Arctic," he said, "these incredible vast open spaces and obviously the stuff we think of — icebergs and glaciers and mountains — and really connected with this desire inside to see more and explore more and to see places really few people get to go explore with my own eyes while I am physically able in this stage in my life."

While in the Arctic on multiple expeditions, Trépanier said he was humbled by a world that he became quickly aware was much bigger than himself.

"It gets down to you, your tent and your hiking boots and opens you up to the world around you," he said. "It is an experience you don't have often unless you get into these types of places."

Challenges of painting in the Arctic

Trépanier photographs, shoots video as well as sketches and paints in oils en plein air while on his trips.

Planning a month-long trip to the high Arctic took more than a year. The year he and his brother visited the national park in the high Arctic, they were the only two official visitors to the park outside of park staff and scientists.

The packs the brothers took on their trip weighed more than 120 ponds each.

"There is that physical nature of going through all this effort of hiking for a day or two and pitching camp to find a place to actually paint," he said. "Then there is a switchover into a creative space to find myself really being able to be on full alert to all the creative potential that is all around me."

The remoteness of such as trip meant the brothers were on their own. They called in daily to relay their position to authorities by satellite phone. But even if they had run into trouble with a bear or other disaster, it would have taken days for help to reach them.

"That remoteness and sense that you are cutting off ties with the rest of the world and being independent on your own is a big part of it, but it is also a part of the allure," Trépanier said.

After dealing with terrain and mosquitoes and blowing sand, he said he hopes his sense of awe and wonder is coming through in his art.

People of the North

Trépanier became friends with some of the Inuit people during his visits to the Arctic. He told the story of spending time with an elder, David.

"I went out on the land with him for a while," he said. "As we walked around, he started to bend over and show me all of these things. He would pick up this plant. 'See this? This is what we make tea with.' 'This is what we make fire with.' And then he picked up this mushroom that was kind of old. 'See this? We use this for cuts.' He demonstrated on one of his cuts how this heals. There is so much to learn. ...

"People often see the void empty spaces of the North. There is nothing there," he said. "It is such a perspective shift when you travel and you realize through these people there is everything. It is a land of bounty."

Trépanier also said the Inuit and the North taught him patience.

"They live with the rhythms of the land," he said of the Inuit.

Living with wildlife

Trépanier also filmed his encounters with wildlife, including three Arctic wolves.

"My brother and I were in a tent, and three Arctic wolves come up to us and surround us. There was nobody anywhere," he said. "They came up to us. They studied us. They looked at each other. I saw because I was filming it all, they were getting into hunting formation.

"That immediate response is kind of primal. Your heart starts to race and you are one with this wild animal that is just curious about us."

The brothers were not allowed to carry guns in the national park in the high Arctic. All they had to defend themselves if they would have been attacked were knives.

Conservation message

Trépanier also encountered multiple polar bears while in the Arctic, although from a safer distance.

He said he hoped by exposing people to the landscapes in which these animals live will spur the public to protect both the land and the creatures who live in it.

"As an artist, although I am not painting polar bears, it is very much my hope my work of documenting these environments through my paintings helps people connect with these places more and maybe even fall in love with them a bit," he said.

"And then engage in the conversation of what is happening in the North and how it is affecting the wildlife, the environment and the people. I think art can touch people if it is done in a certain way."

Trépanier said people are itching to get at the resources in the Arctic, which is a great concern to him.

"There is the science over here and people are disconnected to it," he said. "With the art, you get engaged with these places that are real and are passionate. Then this science becomes of interest and relevant to this audience who has maybe never spent any time hearing about it at all."

Capturing a moment in time

Although Trépanier did not set out to for his art to documentary in nature, he said he believes it may have evolved to that.

He has only been able to revisit one site — Coronation Glacier — and even in that 11-year interim, the loss of ice was obvious.

"In my lifetime, if I go back there in 30 years, what will be left?" he said. "How much will this place have changed in my own lifetime?"

Trépanier has also partnered with writers on the Arctic for a coffee table book, also titled "Into the Arctic," which is set to be released soon.

You can also follow Trépanier on Facebook, where he regularly hosts live chats from his studio in Ontario.